Painting by numbers

In the first of an occasional series, revisiting classic books with connections to Dumfries & Galloway, Lee Randall takes a journey back to the Golden Age of crime with Dorothy L Sayers' The Five Red Herrings

---

I admire Dorothy L Sayers and crush madly on Lord Peter Wimsey every which way - on the page, incarnated by Ian Carmichael and again by Edward Petherbridge. I know that it was cited as one of the 10 best Galloway books by historian and critic Jack Hunter at the 2005 Wigtown Book Festival.

But, though I’ve read it twice, I cannot love The Five Red Herrings.

There, I’ve said it.

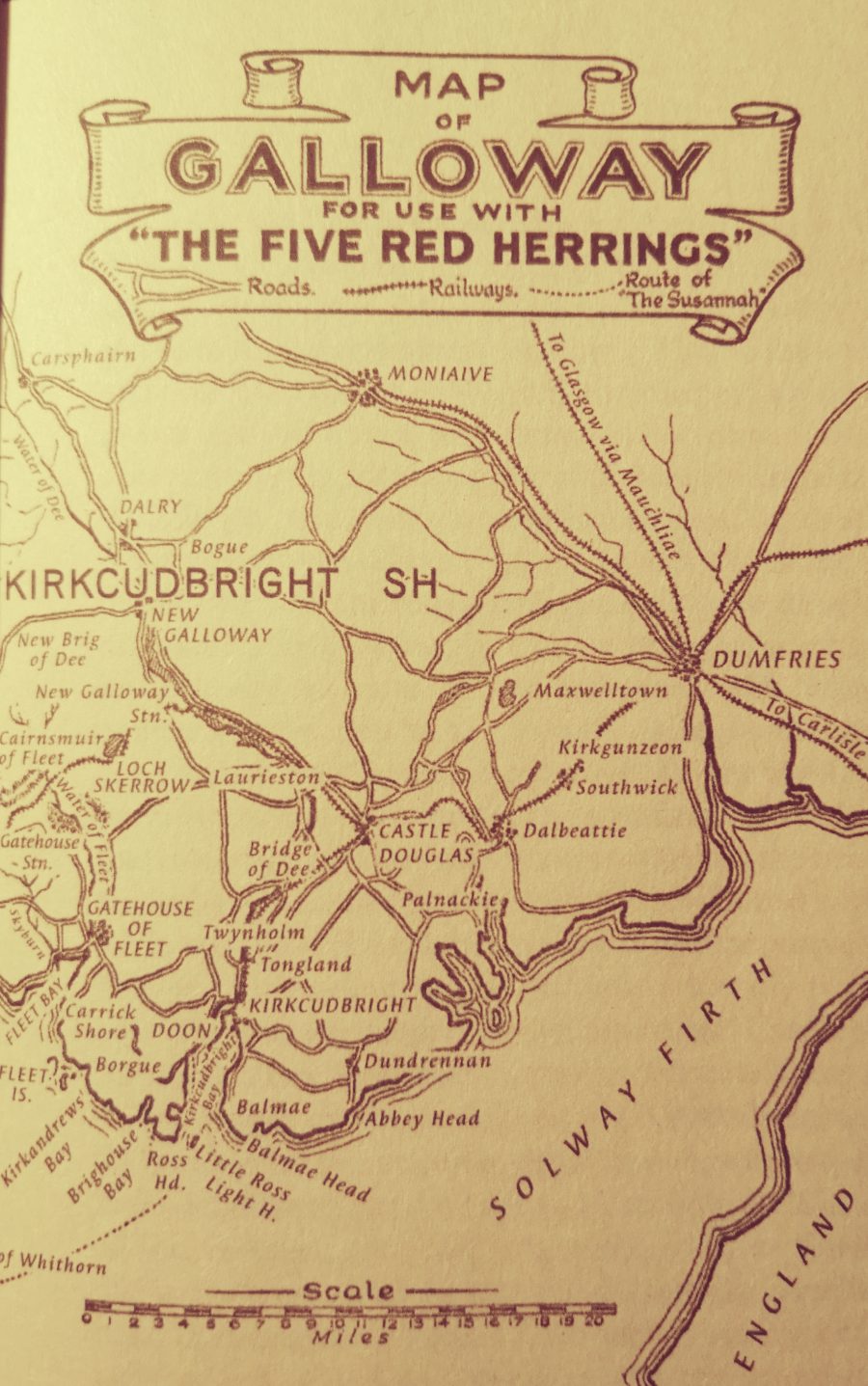

I want to love the novel, published by Gollancz in 1931, and the sixth to feature Lord Peter Wimsey. I should love a book combining two of my favourite things, Golden Age crime and Dumfries & Galloway. The signs are promising: Sayers starts strong, delivering a couple of evocative paragraphs about life in Galloway and the artists’ colony of Kirkcudbright, “where the painters form a scattered constellation, whose nucleus is in the High Street, and whose outer start twinkle in remote hillside cottages, radiating brightness as far as Gatehouse-of-Fleet.”

This is a region Sayers knew intimately from frequent visits with her husband, Oswald Arthur Fleming (an Orkney-born journalist who wrote under the name Atherton Fleming), who was a keen fisherman and artist. Martin Edwards, in his fascinating study, The Golden Age of Murder (Harper Collins, 2015), tells us: “Mac Fleming ... loved speeding at eighty miles an hour along the Kirkcudbright-to-Gatehouse road, much to the horror of his wife, trapped in the passenger seat. Their Scottish holidays prompted Sayers to set a novel in an artistic community in Galloway, where Wimsey stumbles across a murdering a fishing trip.”

Sayers dedicated the novel to Joe Dignam, “kindliest of landlords,” who ran what was then the Anwoth Hotel, in Gatehouse-of-Fleet, where she and her husband stayed, and developed a passion for his wife’s potato scones. (The hotel became the Ship Inn, and went on the market, in 2015. Trivia lovers might want to know that it's where Britt Ekland and Edward Woodward stayed while filming The Wicker Man.)

Her dedication explains, “All the places are real places and all the trains are real trains, and all the landscapes are correct, except that I have run up a few new houses here and there.”

The story finds Wimsey and his devoted manservant, Bunter, returning to holiday in Kirkcudbright, where locals tolerate him because he has no artistic pretensions and “could make a respectable [fishing] cast, and therefore, though English and an 'incomer,’ gave no cause for offence ... True his accent was affected and his behaviour undignified to a degree, but he had been weighed in the balance over many seasons and pronounced harmless, and when he indulged in any startling eccentricity, the matter was dismissed with a shrug and a tolerant, ‘Christ, it’s only his lordship.’”

Wimsey’s relaxed holiday is disrupted by the murder of an unpopular local landscape artist, Sandy Campbell, first seen having a meltdown in the McClellan Arms where he picks a fight with another artist called Waters, who’s English. Less than 24 hours later Campbell is found face down in the Minnoch by Borgan, at the bottom of a steep cliff.

It looks like an accident - surely he stepped back to admire his canvas and lost his footing on the rocks? Still, the doctor notices that rigor seems too pronounced to square with any timing that accounts for the wet, unfinished painting on the easel. Could cold water have made him a stiffer stiff? Wimsey’s unconvinced, and after a recce of the area around Campbell’s easel, pronounces it murder.

There are six prime suspects, artists all. Each man offers up a wildly outlandish story as an alibi - including one who’s been forcibly shorn of his trademark beard, and hies off to London because he’s too ashamed to show his ferret-like features. Every time someone gives an account of himself the story changes, and every suspect’s story embellishes or demolishes the version we’ve read before, making for a tangle of confusion.

The novel benefits from the marvellously hectic energy that’s characteristic of Golden Age crime. People whizz about endlessly. Sayers offers an amusing rendition of the animosity between the English and the Scots, and I can just about gloss over her sole use of the N-word as being reprehensible but of its time. Less bearable is her use - to my mind, abuse - of dialect, which renders her Scottish characters risible. I’d wager some readers will find these characters impenetrable and miss out on chunks of the story. Try this on for size: “Ay, imph’m. The folk at the Borgan seed him pentin’ there shortly after 10 this morning on the wee bit high ground by the brig, and Major Dougal gaed by at 2 o’clock wi’ his rod an’ spied the body liggin’ in the burn ... I’m thinking he’ll ha’ climbed doon tae fetch some water for his pentin’, mebbe, and slippit on the stanes.’” Surely she could have conveyed the flavour of the region by mixing Scots words and cadences with standardised spelling.

This “pure puzzle mystery,” sees Wimsey and co nipping around Galloway by car, bicycle and train. Endlessly, by train. Tediously, by train. The plot relies on actual distances and real timetables, not only for the local region, but along routes to Glasgow and London, as well. Timetables are even printed in the text, lest we miss a minute. It’s said that every sentence of this novel is crucial to plot, but it was tough keeping my eyes from skipping across the pages, past endless times and routes, on the lookout for another lyrical description, or entertaining encounter between Bunter and Wimsey.

Think I’m exaggerating? Here’s an example: “He had not gone on to Glasgow by the 1.54, because it was quite certain that the bicycle could not have been re-labelled before the train left. There remained the 1.56 to Muirkirk, the 2.12 and the 2.23 to Glasgow, the 2.30 to Dalmellington, the 2.35 to Kilmarnock and the 2.45 to Stranraer, besides, of course, the 2.25 itself.”

In the margins I see I’ve scribbled: “FFS.”

How ironic that this story with its focus on transport isn’t transporting. To me, and to past reviewers, including MI Cole, writing in The Spectator when this was released, the novel is tedious and taxing, flat and dull, with practically indistinguishable characters. And I speak as an avid crossword solver, who begins every morning at the New York Times’ puzzle page. It’s a disappointment, because Sayers’ writing is usually as lively, engaging, and entertaining as her great creation, Lord Peter Wimsey.

Nevertheless, for those with a nostalgic bent, The Five Red Herrings is illuminating - even poignant - in its descriptions of the myriad possibilities that once existed for travel in and out of Galloway, prior to the Beeching cuts that did away with most of these train lines when they eliminated around 650 miles of railway in Scotland.

What infuriates me most is that the vital clue alerting Wimsey that Campbell’s death isn't accidental, and leading him to deduce which of the six artists did it, has nothing to do with travel. Not a bit. Standing at the cliff’s edge inspecting the scene - Campbell’s belongings, and the start of an oil painting, “a striking piece of work, bold in its masses and chiaroscuro, and strongly laid on with the knife” - Wimsey notices that something he expects to be there isn’t. Readers who know about art will spot the problem, but everyone else will probably be frustrated to read: “(Here Lord Peter Wimsey told the Sergeant what he was to look for and why, but as the intelligent reader will readily supply these details for himself, they are omitted from this page.)”

Those endless timetables don’t tell Wimsey whodunnit, they’re how he proves it. At that point, having been literally around the houses a dozen times by train, I wished he’d just beaten a confession out of the man many pages earlier.

In their Edgar-award winning book about the genre, A Catalogue of Crime (Harper & Row 1971, revised in 1989), Jacques Barzun and Wendell Taylor praise The Five Red Herrings as "a work that grows on rereading and remains in the mind as one of the richest, most colourful of her group studies. The Scottish setting, the artists in the colony, the train-ticket puzzle, and the final chase place this triumph among the four or five chefs d'oeuvre from her hand”.

Well, I’ve read it twice, and disagree. Read the other Wimsey novels, which are delightful. Tackle this one if you’re a completist.

Aside: The BBC’s four-part series of the novel - filmed in Kirkcudbright, and using dialogue straight from the novel - solved many of the issues I have with the text. The clue Wimsey notices at the murder site is openly stated and the actors’ Scottish accents are comprehensible and dignified, adding colour and veracity instead of comedy. For interiors buffs, there’s the added bonus of a set designer who went Mackintosh-mad when constructing the Farren’s cottage.