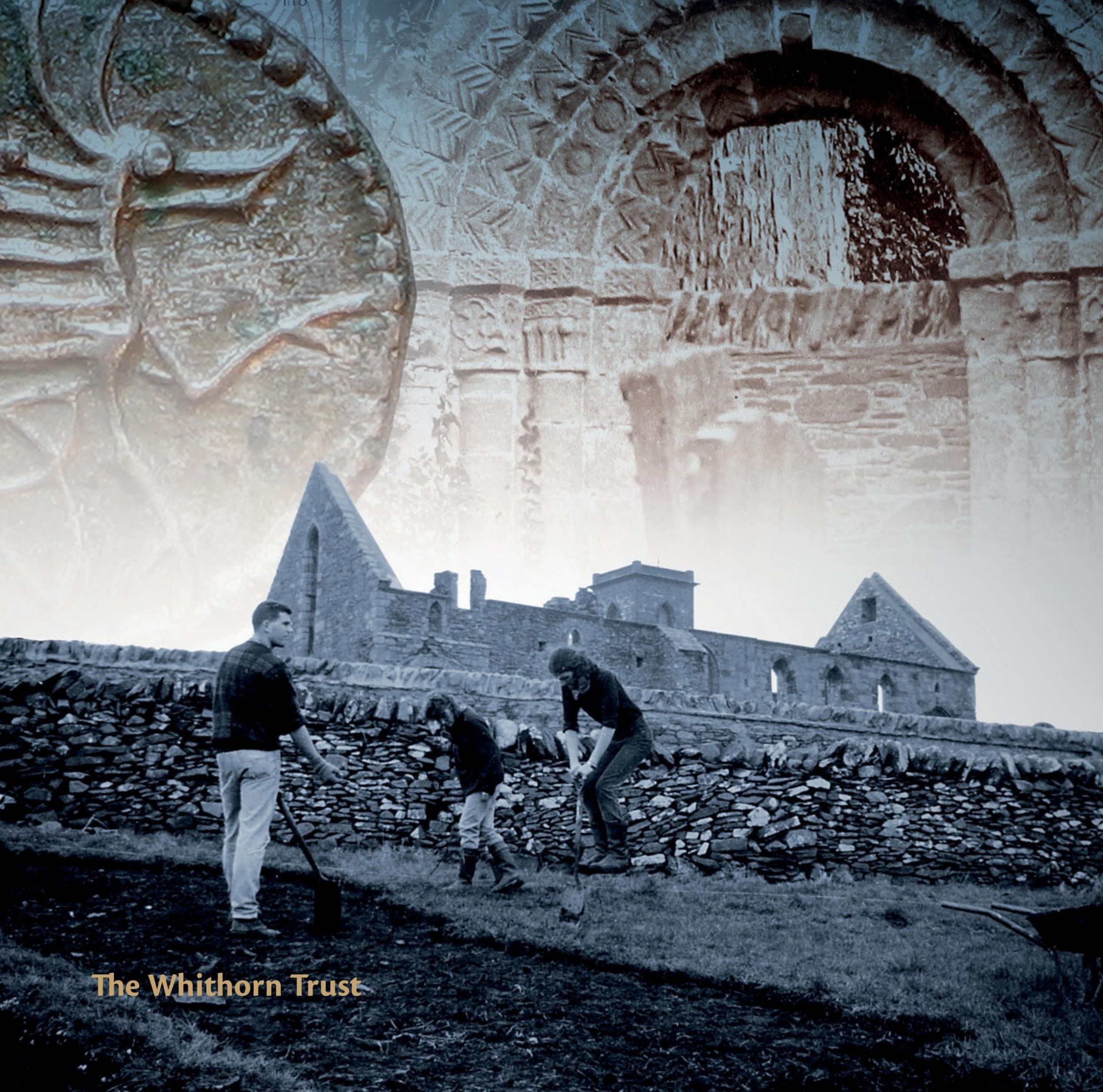

Cold Case Whithorn Project

Multitude of discoveries about life in and around the ancient church and monastery at Whithorn with Adrián Maldonado from National Museums Scotland

Festival audiences love to hear about Cold Case Whithorn project, which has made a multitude of discoveries about life in and around the ancient church and monastery at Whithorn.

This year’s Whithorn Trust event sees Adrián Maldonado, from National Museums Scotland, discuss a new concise guidebook that explores what we now know about life there from the fifth to twelfth centuries.

I’m truly thrilled to be speaking at this year’s Wigtown Book Festival on a project that has been years in the making.

More than 40 years ago now, excavations began at Whithorn which would lead to the first-ever large-scale excavation of an early monastic burial ground in Scotland. The remarkable finds from that dig included what is still the earliest dated physical church in Scotland, trade items from as far as the eastern Mediterranean and the formation of one of the earliest urban centres in northern Britain.

For the last few years, I’ve been part of a team of researchers and museum professionals working with the Whithorn Trust on the Cold Case Whithorn project, which has transformed the potential of this incredible archive. And for the first time since 1991, we have now produced a guidebook to the early medieval archaeology, richly illustrated and affordable – and in plain English, too!

Focus on Whithorn’s earliest people

The monumental publication that followed the excavations – Peter Hill’s Whithorn and St Ninian: the Excavation of a Monastic Town, 1984-91 (1997) – is 656 pages long and packed with data, to which we only added with our recent work. So we decided to focus on the early medieval period from the fifth to the twelfth centuries, and put the earliest inhabitants of Whithorn in context.

While Whithorn was the first early monastery in Scotland to be investigated at that scale, the decades since have now seen major discoveries at monasteries like Iona, Hoddom, Auldhame, Portmahomack and the Isle of May. My own doctoral research brought these finds together and devoted a chapter to the new questions they raised for Whithorn.

As with any museum, the majority of the Whithorn assemblage is safely curated off-display to enable future research. My interest in the site coincided with a push to bring the archive up to modern standards, including a comprehensive repackaging of archaeological materials and a renewed digital archive. In 2018, we began the Cold Case Whithorn project which combined a complete overhaul of the archive with a focus on the collection of human remains. Through this we have gained incredible new insights on the formation of the early monastery and the town that grew up around it.

Centuries of craft and trade

After years of thinking intensely about Whithorn, it was kind of fun – but hard work – compressing it all into a 36-page guidebook. Getting down to the very gist of why things are important is a useful skill that every archaeologist and historian needs to keep sharp.

And writing the guidebook made me rethink some of my own assumptions, and notice small but important things I’d overlooked. For instance, the earliest phases of settlement in the Glebe Field were constantly shifting – first there’s plough marks, then ephemeral huts, then graves, then a Viking market-town. But one thing that is consistent across all these phases is a roadway or an avenue cutting across the archaeological trench, which invariably led up the hill to where the medieval church is today. It is a reminder that the centuries of trade, craftworking, worship and funerary activity unearthed here were always just a slice of life around the main focus of the site, which is presumably the earliest shrine of St Ninian.

The core of the Glebe Field site appears to have been the odd little burial chapel that was built there in the early eighth century, when the old monastery was overhauled by the incoming Northumbrian rulers. It was built within an existing burial ground, and according to our new radiocarbon dates, some of these graves were very recent. One grave outside the new chapel contained jumbled-up bones, presumably of a burial disturbed by these works.

Unique chapel burned in the Viking Age

This chapel was and remains unique. Founded in dry stone, it carried walls of clay and timber. The east wall had an opening which was glazed with multi-coloured panes: Scotland’s first stained glass window. Only five burials were allowed to take place inside the chapel over the next century or so; at least one of these was a woman. These burials were themselves unique, in decorated and padlocked chests rather than the usual coffins.

This chapel was burned down in the thick of the Viking Age – though the case of who did it remains cold. But importantly, it was rebuilt on the same footprint, showing continuity of the community here. The nearby Galloway Hoard reminds us of the wealth that still remained in Northumbrian hands in this region by the year c 900.

It is a great honour to try and inspire another generation of interest in this incredible site and share these insights with the tons of school groups, walkers, pilgrims and visitors from around the globe that come to Whithorn every year.

The PDF of the 2025 Wigtown Book Festival programme can be downloaded here, or book your tickets online.